Tuesday, January 2, 2024

2023 publications on teachers use of action research in Bhutan (a few more to be released)

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Cycles Within Cycles: Three Minutes Thesis Presenatation

Recently, there has been a growing interest in action research in Bhutan, a small developing, Buddhist country in South Asia, as a tool to raise teaching quality and the quality of education. However, the questions are: Is action research relevant for Bhutanese teachers? How would Bhutanese teachers conduct the process of action research? What factors influence the way they conduct action research? My study aimed at answering these questions. To answer the questions, I focused on two case study schools where three secondary science teachers conducted their first-ever action research. I observed how they followed the process and recorded their experience through interviews and reflective diaries.

Such findings suggested a need to improve the school context and put a new model in place. Therefore, my study will be proposing a new action research model for Bhutanese science teachers. I am hopeful that the model will help the science teachers in Bhutan to conduct action research confidently, enhance their teaching quality, raise the quality of science education and, more broadly, contribute towards achieving the UN sustainable development goal of providing quality education for all.

Thursday, March 18, 2021

With Professor Stephen Kemmis

Action research is relatively new in Bhutan. Emeritus Professor Stephen Kemmis' (1988) well-known spiral action research model is advocated for teachers in Bhutan to use it to improve their teaching practices. In my doctoral study, I explore the relevance of this model to the Bhutanese Secondary Science teachers. I was fortunate to meet Professor Stephen at Monash last year at a masterclass. In the brief chat, I let him know of my project. He expressed his interest to read my final work. I would like to thank him for sharing some of his recent works on action research. It has helped to take my project forward.

Wednesday, February 17, 2021

Teachers' Pedagogical Practices in Bhutan: Transcription of V-TOB Edutalk

Upon V-TOB's (Volunteer Teachers of Bhutan) invitation to participate in a discussion on "Quality Teachers for Quality Learning" on 6th February 2021, I spoke on "Teachers Pedagogical Practices in Bhutan" drawing on my experience as a teacher. I watched the recorded video and the following is a verbatim transcription of my talk on the subject.

1. Introduction

Kuzu Zangpola everyone. I am Tshewang Rabgay and I am a PhD student in Education at Monash University in Australia la. Firstly, I would like to thank sir Sonam for having me this evening on V-TOB’s Edutalk. Secondly, it is an honour to be sharing the panel with Sir KC Jose who is a renowned teacher and had a long teaching career in Bhutan and with Sir Tshedrup Dorji, the founder of YAN Bhutan la.

2. Body

Well! The theme for today’s Edutalk is quality teacher for quality learning, a very important subject but it is a broad area to talk about in ten minutes, so I needed to narrow it down la. I looked at some frameworks around teacher quality and found that there are several components that make a great teacher.

I decided to focus on one component instead of going all over. So I will talk on a single component of teacher quality la. I have chosen teaching practices or teachers’ pedagogical practices. And I will be talking on this subject by drawing on some studies and my experience la. I think I have quite a lot to share in ten minutes and I will try to be as fast as possible.

Well, this is a subject which most of us are familiar with

because it has been an area of focus in many public and academic discourses for

quite a while and I might sound a bit cliché today and may have nothing much to

offer but I will just share my ideas la. But it is a subject that has

persistently remained stagnant or had a very slow progress in practice la. Even in an earlier Edutalk I remember Dr. Adrian mentioning “pedagogical

poverty”, hence, I believe that it still needs further discussion and debate

and more so in the context of current education reform la.

Well! It is common knowledge that teachers’ pedagogical practices determine the quality of teaching and learning. However, the narrative that all of us familiar around teachers’ pedagogical practice in Bhutan is that there is a need for a shift from the predominant teacher-centered teaching to more child-centered or constructivist-based teaching to raise the quality of education. I gathered some studies on this area and I found that there is a large body of literature suggesting the need for a shift la.

Then there has also been efforts from the MoE and the

teacher education colleges to educate both in-service and pre-service on

child-centered teaching techniques. The prominent one is the introduction of CL

method in 2016 through the Transformative Pedagogy program. And there are

others such as placed based education, etc. And the Government puts a lot of

financial investment, for example, I got this statistics that in 2010 and

2011 alone, the Government spend Nu. 24.9 millions on pedagogy-related training

for some 2,554 teachers.

Moreover, the teacher education colleges provide opportunities for pre-service teacher to learn several child centered teaching methods such as: activity method, field learning, inquiry method, cooperative learning, role play and simulation. Most teachers would remember the micro-teaching we did at the colleges to practice these techniques. Therefore, it is clear that teachers have the knowledge and skills to apply constructivist teaching techniques.

Despite these efforts, studies continue to show that teacher-centered teaching is still the most widely used method, indicating stagnation or a slow progress. Now the question is: Why is there a visible stagnation? Or why has there been a slow progress? I attribute it to five constraining factors la. However, the reasons that I am going to be sharing are not founded on any research, they are based on my experience and observations and I stand corrected if they are inappropriate la.

2.1 Lack of teacher generated pedagogical knowledge

The first reason I would like to propose is that there is a lack of teacher-generated pedagogical knowledge to inform their practices in Bhutan la. There is an absence of teacher voices on issues related to their teaching practices from a truly emic perspective and the teaching profession suffers, from “a shaky theoretical ground.’ This has resulted in three consequences:

1. Firstly,

teachers rely on out-of-school professionals in higher authorities or foreign

experts to inquire into their teaching practices. Teachers are knowledge

consumers and not knowledge generators and the knowledge generated by outsiders

may not be all the time relevant to address the context specific issues they

face in the classroom.

2. Secondly,

teachers rely on out of-school PD activities such as workshops and trainings to

gain knowledge related to their teaching. Again, knowledge obtained through

such means may not be relevant to the contextual realities of their classroom

teaching.

3. Thirdly,

the everyday classroom decisions that teachers make are based on their

intuitions, assumptions, hearsay, verbal advice, and latest fads which do not

guarantee success.

Therefore, there is a need for teachers to inquire into

their practices to generate knowledge on what works and what do not work in

their classrooms. Teachers need to explore whether the foreign

constructivist teaching models works in their classrooms or not, instead of

just accepting it. And find solid reasons for why these approaches work or do

not work. And think of what adjustments are required to make the foreign model

relevant.

One of the ways to do this is by empowering teachers to

carry out action research or conventional teacher research which is a

self-reflective tool that allows teachers to systematically inquire into their

practices. It is encouraging to note that the MoE and the teacher education

colleges are promoting action research. However, I have observed that most

teachers are not confident to follow the process of action research. This could

partly be because we have a foreign model and there is a question of the

relevance of the model. A part of my current research concerns this area la and

I am hoping that the findings will have implications in assisting Bhutanese

teachers to carry out action research confidently.

However, my suggestion at this point is, for the school

leaders and the MoE to create and foster a sound research culture in schools

which I believe is lacking at the moment la. There is a need to strengthen

action research courses in the teacher education colleges. There is a need

for teacher to take the role as reflective practitioners and gear towards

transforming teaching into a research-based profession la.

In carrying out classroom research, teachers have a distinct advantage over out-of-school researchers. Their position as insiders who know their classroom culture and their students give them the upper hand in finding specific and relevant solutions to their pedagogical issues, over outsiders who would not be as much familiar with the classroom realities. The other advantage I see in Bhutan is that teachers make up a large proportion of the total civil servants, I guess, 34.9%. If most teachers engage in action research, a rich and diverse pedagogical knowledge base would be generated in a short period, thereby laying a solid theoretical foundation to underpin the teaching profession in Bhutan la.

I will give you an example of UK. In the 1970s, that’s some five decades ago, there was a movement called the “Teachers as Researchers” movement initiated by Professor Lawrence Stenhouse that called for teachers to research into their practices. This movement had a remarkable impact on raising teacher quality. Teachers were able to base their classroom decisions on data and evidence and raise their teaching quality. They could also play active roles in curriculum development.

2.2 Curriculum as a barrier

The second reason is an obvious one. The existing school

curriculum is inappropriate for teachers to apply their constructivist

pedagogical knowledge and skills. I have been listening to practically all

previous EDUTALKs and most speakers generally agreed that Bhutan’s school

curriculum is content-overloaded. And the other day, Sir Sancha Rai and madam

Ambika also described the school curriculum as bulky, thick, prescriptive,

rigid and centralized.

The thick curriculum hardly provides time and space for the

teachers to apply their constructivist pedagogical knowledge. It rather forces

them to use teacher-centered teaching to fulfil the mandate of completing the

syllabus.

Therefore, what is needed at the moment is a curriculum that is designed from constructivist point of view to match up with teachers’ constructivist pedagogical knowledge and a curriculum that provides time and space for teachers to use their constructivist pedagogical knowledge without any pressure of completion.

Last week, there was some news of the REC taking some steps towards this la. However, there are still questions around its flexibility or whether it was just a cutting-down exercise of the previous curriculum, questions around inadequate teacher consultation and information, but I will not dwell much on this la.

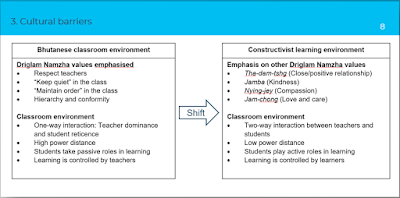

2.3 Cultural barriers

The third reason could be due to cultural barriers.

Child-centered teaching is mostly popular in Euro-American countries where the

culture is different from our culture in Bhutan. And it is a teaching approach

that has worked well when teachers create a learning environment of open,

critical and two-way interaction between teachers and students or between the

students.

This nature of child centered teaching approach contradicts

some of the cultural values that we uphold. In particular Driglam Namzha or the

Bhutanese code of etiquette which is an important part of our social lives.

Driglam Namzha has its roots in Kangyur Dulwa, Buddha’s teaching on monastic

discipline. We promote Driglam Namzha in our schools as a part of school

discipline along with other values such as Tha-Damtshi and Ley Judrey. As

a result, we foster a classroom culture where there is respect for teachers,

where students are reticent to talk with teachers and ask questions, where

there is a high power distance and where teachers prefer student to quietly

listen to them. As Michael Rutland pointed out in an earlier EDUTALK, teachers

in Bhutan often tell students to “keep quiet” or “maintain order”. These

cultural elements contradicts the principles of constructivist teaching such as

open and active classroom interaction and students taking control of their

learning,

That is why it would have been hard for teachers to make the

transition to the new pedagogical approach because it needs letting go off of

our cultural values and embracing different kind of mindset and roles. And

not only teachers la, it also needs students to make a radical shift in their

roles and mindset from being passive to active.

My proposition to address this issue is for the teachers, to

make a conscious effort to embrace a new set of Driglam Namzha values. We

should know that Driglam Namzha is not limited to the etiquette of respecting

seniors. It also concerns the etiquette of following the principles of

Tha-dam-tshig, Ley-judrey, Jamba and Nyingjey. At the moment the predominant

and lopsided value that plays out in the class is respect for teachers, which

is also important but I suggest the teachers also emphasize on other Driglam

Namzha values such as:

· Tha-dam-tshig

(which refers to a close or positive relationship between teachers and students

· Jamba or

Kindness

· Nying-Jey or

Compassion

· Jam-Chong or

Love and care

These values would enable teachers to create a warm and friendly classroom environment which is what is required for child-centered teaching. Along with this the teachers need to step out of their conventional role of being the dominant figure in the class to taking the role of a guide and supporter through carefully planned lessons and engage in active interaction with students.

2.4 Teacher pedagogical beliefs, conceptions and memory

The other possible reason could be teachers’ pedagogical

conception and memory. Human experience shapes their conceptions and memories

which in turn drives their actions.

Most of our teachers, including myself, have along

experience of being taught in a teacher-fronted teaching environment when we

were students, in schools and later in pre-service teacher education

colleges and our pedagogical conceptions are largely around

teacher-fronted teaching. It could be because of this deep rooted conception

that most teachers find it hard to drop the old habit.

When we ask students, their ambitions in the class, some of

them would say that they would want to be teachers. We think that teacher

preparation and teacher education occurs only at teacher education colleges but

I would say that it happens even at schools because there are students who want

to be teachers and they observe the way their teachers teach them in their

class. Then the question that teachers need to ask is: “Do we practice the

right pedagogy so that future teachers have the right pedagogical conceptions?”

At the moment most teacher practice teacher centred teaching and it is likely

that the future teachers will continue the practice because their pedagogical

conception might largely be around teacher-centred teaching. So, we need to

break the chain. We need to stop passing the bug on to future teachers.

My recommendation on this is for the teachers to unlearn some of the ineffective pedagogical approaches and to embark on learning, designing and practicing new, effective and relevant pedagogical approaches, so that our future teachers develop the right pedagogical conceptions for right pedagogical practices.

There are also other issues such as time constraints, class

size, student number, and heavy workload but for now I will keep it here la. And

I am happy to take any questions and suggestions. Thank you la..

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to draw your attention to the Bhutan Professional Standards for teachers (BPST), a document that has been launched to raise teachers' professional standards or in other words teacher quality. The Ministry of Education has specified seven standards for teachers to fulfil and I believe teachers will be assessed against these standards to determine their professional standard la. The third standard concerns demonstration and application of sound pedagogical and content knowledge to facilitate effective teaching and learning.

As mentioned earlier, the ground reality is that there

are certain challenges that hinders teachers from making pedagogical

progress. The curriculum needs revision, there is a need for creating

sound research cultures, and there is a need for providing time flexibility and

adequate resources in the school. I think it would be hard for teachers to

fulfil these standards because at the moment the conditions in the schools are

not right la. Because of these challenges, many teacher friends that talked to

say that the BPST is an additional pressure rather than support from the MOE

la. Most of them are worried about how to find the time to engage in innovative

pedagogical practices within their heavy workloads of covering the heavy

curriculum and carrying out co-curricular activities.

Therefore, I propose the MoE to take a closer look at

teachers' professional lives in the schools first, determine the

feasibility of the plan, create the enabling conditions and then introduce

the standards la. In fact, I believe that this is how it should be for any

education reform initiative la. I will make a simple analogy la.

If parking police want the public to strictly follow the

rule of having their cars parked properly in the parking lots, first they have

to work on making sure that there are enough parking spaces. If there are

limited parking spaces then the rule will just be too much pressure for the

public la. This is a simple example la.

In a nut shell, I believe that placing a flexible

curriculum, creating supportive condition in the school and fostering a culture

of teacher inquiry, would open up the opportunity for teachers to raise their

pedagogical practices which would raise teacher quality and then eventually

raise the quality of learning.

Thank you for listening la and thank you Sir Sonam for the opportunity la.

**********************************************************************************

PS: Here is the link to the video

https://www.facebook.com/volunteers.strength/videos/714250052579270/

Sunday, June 14, 2020

Action Research

Action researchers “see the development of theory or understanding as a by-product of the improvement of real situations, rather than application as a by-product of advances in ‘pure’ theory.” (Carr and Kemmis, 1986, p. 28, cited also in Wikiversity Action Learning article). This is a means to generate ideas (theory) that are relevant locally – to the people who are involved in the research, and to the environment in which it has taken place. (Wikiversity, en.wikiversity.org)

Picture 1: Ary, D., Jacobs. L. C., & Sorensen, C. (2010). Introduction to Research in Education (8th ed). California: Wadsworth.

Picture 3: Hendricks, C. (2017). Improving schools through action research: A reflective practice approach (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Picture 4: McKernan, J. (1996, p.31). Curriculum action research: A handbook of methods and resources for the reflective practitioner. London: Kogan Page.